A pencil (/ˈpɛnsəl/ ⓘ) is a writing or drawing implement with a solid pigment core in a protective casing that reduces the risk of core breakage and keeps it from marking the user’s hand.

Pencils create marks by physical abrasion, leaving a trail of solid core material that adheres to a sheet of paper or other surface. They are distinct from pens, which dispense liquid or gel ink onto the marked surface.

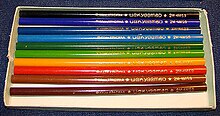

Most pencil cores are made of graphite powder mixed with a clay binder. Graphite pencils (traditionally known as “lead pencils”) produce grey or black marks that are easily erased, but otherwise resistant to moisture, most solvents, ultraviolet radiation and natural aging. Other types of pencil cores, such as those of charcoal, are mainly used for drawing and sketching. Coloured pencils are sometimes used by teachers or editors to correct submitted texts, but are typically regarded as art supplies, especially those with cores made from wax-based binders that tend to smear when erasers are applied to them. Grease pencils have a softer, oily core that can leave marks on smooth surfaces such as glass or porcelain.

Coloured pencils (Caran d’Ache)

The most common pencil casing is thin wood, usually hexagonal in section, but sometimes cylindrical or triangular, permanently bonded to the core. Casings may be of other materials, such as plastic or paper. To use the pencil, the casing must be carved or peeled off to expose the working end of the core as a sharp point. Mechanical pencils have more elaborate casings which are not bonded to the core; instead, they support separate, mobile pigment cores that can be extended or retracted (usually through the casing’s tip) as needed. These casings can be reloaded with new cores (usually graphite) as the previous ones are exhausted.

History

Camel hair

Pencil, from Old French pincel, from late Latin penicillus a “little tail” (see penis; pincellus)[1] originally referred to an artist’s fine brush of camel hair, also used for writing before modern lead or chalk pencils.[2]

Though the archetypal pencil was an artist’s brush, the stylus, a thin metal stick used for scratching in papyrus or wax tablets, was used extensively by the Romans[3] and for palm-leaf manuscripts.

Graphite deposit discoveries

As a technique for drawing, the closest predecessor to the pencil was silverpoint or leadpoint until, in 1565 (some sources say as early as 1500), a large deposit of graphite was discovered on the approach to Grey Knotts from the hamlet of Seathwaite in Borrowdale parish, Cumbria, England.[4][5][6][7] This particular deposit of graphite was extremely pure and solid, and it could easily be sawn into sticks. It remains the only large-scale deposit of graphite ever found in this solid form.[8] Chemistry was in its infancy and the substance was thought to be a form of lead.[citation needed] Consequently, it was called plumbago (Latin for “lead ore“).[9][10] Because the pencil core is still referred to as “lead”, or “a lead”, many people have the misconception that the graphite in the pencil is lead,[11] and the black core of pencils is still referred to as lead, even though it never contained the element lead.[12][13][14][15][16] The words for pencil in German (Bleistift), Irish (peann luaidhe), Arabic (قلم رصاص qalam raṣāṣ), and some other languages literally mean lead pen.

The value of graphite would soon be realised to be enormous, mainly because it could be used to line the moulds for cannonballs; the mines were taken over by the Crown and were guarded. When sufficient stores of graphite had been accumulated, the mines were flooded to prevent theft until more was required.[citation needed]

The usefulness of graphite for pencils was discovered as well, but initially graphite for pencils had to be smuggled out of England. Because graphite is soft, it requires some form of encasement. Graphite sticks were initially wrapped in string or sheepskin for stability. England would enjoy a monopoly on the production of pencils until a method of reconstituting the graphite powder was found in 1662 in Germany. However, the distinctively square English pencils continued to be made with sticks cut from natural graphite into the 1860s. The town of Keswick, near the original findings of block graphite, still manufactures pencils, the factory also being the location of the Derwent Pencil Museum.[17] The meaning of “graphite writing implement” apparently evolved late in the 16th century.[18]

Wood encasement

Around 1560,[19] an Italian couple named Simonio and Lyndiana Bernacotti made what are likely the first blueprints for the modern, wood-encased carpentry pencil. Their version was a flat, oval, more compact type of pencil. Their concept involved the hollowing out of a stick of juniper wood. Shortly thereafter, a superior technique was discovered: two wooden halves were carved, a graphite stick inserted, and the halves then glued together—essentially the same method in use to this day.[20]

Graphite powder and clay

The first attempt to manufacture graphite sticks from powdered graphite was in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1662. It used a mixture of graphite, sulphur, and antimony.[21][22][23]

English and German pencils were not available to the French during the Napoleonic Wars; France, under naval blockade imposed by Great Britain, was unable to import the pure graphite sticks from the British Grey Knotts mines – the only known source in the world. France was also unable to import the inferior German graphite pencil substitute. It took the efforts of an officer in Napoleon‘s army to change this. In 1795, Nicolas-Jacques Conté discovered a method of mixing powdered graphite with clay and forming the mixture into rods that were then fired in a kiln. By varying the ratio of graphite to clay, the hardness of the graphite rod could also be varied. This method of manufacture, which had been earlier discovered by the Austrian Joseph Hardtmuth, the founder of the Koh-I-Noor in 1790, remains in use. In 1802, the production of graphite leads from graphite and clay was patented by the Koh-I-Noor company in Vienna.[24]

In England, pencils continued to be made from whole sawn graphite. Henry Bessemer‘s first successful invention (1838) was a method of compressing graphite powder into solid graphite thus allowing the waste from sawing to be reused.[25]

United States

American colonists imported pencils from Europe until after the American Revolution. Benjamin Franklin advertised pencils for sale in his Pennsylvania Gazette in 1729, and George Washington used a three-inch (7.5 cm) pencil when he surveyed the Ohio Country in 1762.[26][better source needed] William Munroe, a cabinetmaker in Concord, Massachusetts, made the first American wood pencils in 1812. This was not the only pencil-making occurring in Concord. According to Henry Petroski, transcendentalist philosopher Henry David Thoreau discovered how to make a good pencil out of inferior graphite using clay as the binder; this invention was prompted by his father’s pencil factory in Concord, which employed graphite found in New Hampshire in 1821 by Charles Dunbar.[7]

Munroe’s method of making pencils was painstakingly slow, and in the neighbouring town of Acton, a pencil mill owner named Ebenezer Wood set out to automate the process at his own pencil mill located at Nashoba Brook. He used the first circular saw in pencil production. He constructed the first of the hexagon- and octagon-shaped wooden casings. Ebenezer did not patent his invention and shared his techniques with anyone. One of those was Eberhard Faber, which built a factory in New York and became the leader in pencil production.[27]

Joseph Dixon, an inventor and entrepreneur involved with the Tantiusques graphite mine in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, developed a means to mass-produce pencils. By 1870, The Joseph Dixon Crucible Company was the world’s largest dealer and consumer of graphite and later became the contemporary Dixon Ticonderoga pencil and art supplies company.[28][29]

By the end of the nineteenth century, over 240,000 pencils were used each day in the US. The favoured timber for pencils was Red Cedar as it was aromatic and did not splinter when sharpened. In the early twentieth century supplies of Red Cedar were dwindling so that pencil manufacturers were forced to recycle the wood from cedar fences and barns to maintain supply.[citation needed]

One effect of this was that “during World War II rotary pencil sharpeners were outlawed in Britain because they wasted so much scarce lead and wood, and pencils had to be sharpened in the more conservative manner – with knives.”[30]

It was soon discovered that incense cedar, when dyed and perfumed to resemble Red Cedar, was a suitable alternative. Most pencils today are made from this timber, which is grown in managed forests. Over 14 billion pencils are manufactured worldwide annually.[31] Less popular alternatives to cedar include basswood and alder.[30]

In Southeast Asia, the wood Jelutong may be used to create pencils (though the use of this rainforest species is controversial).[32] Environmentalists prefer the use of Pulai – another wood native to the region in pencil manufacturing.[33][34]

Eraser attachment

On 30 March 1858, Hymen Lipman received the first patent for attaching an eraser to the end of a pencil.[35] In 1862, Lipman sold his patent to Joseph Reckendorfer for $100,000, who went on to sue pencil manufacturer Faber-Castell for infringement.[36] In Reckendorfer v. Faber (1875), the Supreme Court of the United States ruled against Reckendorfer, declaring the patent invalid.[37]

Extenders

Main article: Pencil extender

Historian Henry Petroski notes that while ever more efficient means of mass production of pencils has driven the replacement cost of a pencil down, before this people would continue to use even the stub of a pencil. For those who did not feel comfortable using a stub, pencil extenders were sold. These devices function something like a porte-crayon…the pencil stub can be inserted into the end of a shaft…Extenders were especially common among engineers and draftsmen, whose favorite pencils were priced dearly. The use of an extender also has the advantage that the pencil does not appreciably change its heft as it wears down.[30] Artists use extenders to maximize the use of their colored pencils.

Types

By marking material

Graphite

Graphite pencils are the most common types of pencil, and are encased in wood. They are made of a mixture of clay and graphite and their darkness varies from light grey to black. Their composition allows for the smoothest strokes.

Solid

Solid graphite pencils are solid sticks of graphite and clay composite (as found in a ‘graphite pencil’), about the diameter of a common pencil, which have no casing other than a wrapper or label. They are often called “woodless” pencils. They are used primarily for art purposes as the lack of casing allows for covering larger spaces more easily, creating different effects, and providing greater economy as the entirety of the pencil is used. They are available in the same darkness range as wood-encased graphite pencils.

Liquid

Liquid graphite pencils are pencils that write like pens. The technology was first invented in 1955 by Scripto and Parker Pens. Scripto’s liquid graphite formula came out about three months before Parker’s liquid lead formula. To avoid a lengthy patent fight the two companies agreed to share their formulas.[38]

Charcoal

Charcoal pencils are made of charcoal and provide fuller blacks than graphite pencils, but tend to smudge easily and are more abrasive than graphite. Sepia-toned and white pencils are also available for duotone techniques.

Carbon pencils

Carbon pencils are generally made of a mixture of clay and lamp black, but are sometimes blended with charcoal or graphite depending on the darkness and manufacturer. They produce a fuller black than graphite pencils, are smoother than charcoal, and have minimal dust and smudging. They also blend very well, much like charcoal.

Colored

Colored pencils, or pencil crayons, have wax-like cores with pigment and other fillers. Several colors are sometimes blended together.[39]

Grease

Grease pencils can write on virtually any surface (including glass, plastic, metal and photographs). The most commonly found grease pencils are encased in paper (Berol and Sanford Peel-off), but they can also be encased in wood (Staedtler Omnichrom).[39]

Watercolor

Watercolor pencils are designed for use with watercolor techniques. Their cores can be diluted by water. The pencils can be used by themselves for sharp, bold lines. Strokes made by the pencil can also be saturated with water and spread with brushes.[39]

By use

Carpentry

Carpenter’s pencils are pencils that have two main properties: their shape prevents them from rolling, and their graphite is strong.[40] The oldest surviving pencil is a German carpenter’s pencil dating from the 17th Century and now in the Faber-Castell collection.[41][42]

Copying

Copying pencils (or indelible pencils) are graphite pencils with an added dye that creates an indelible mark. They were invented in the late 19th century for press copying and as a practical substitute for fountain pens. Their markings are often visually indistinguishable from those of standard graphite pencils, but when moistened their markings dissolve into a coloured ink, which is then pressed into another piece of paper. They were widely used until the mid-20th century when ball pens slowly replaced them. In Italy their use is still mandated by law for voting paper ballots in elections and referendums.[43]

Eyeliner

Eye liner pencils are used for make-up. Unlike traditional copying pencils, eyeliner pencils usually contain non-toxic dyes.[44]

Erasable coloring

Unlike wax-based colored pencils, the erasable variants can be easily erased. Their main use is in sketching, where the objective is to create an outline using the same color that other media (such as wax pencils, or watercolor paints) would fill[45] or when the objective is to scan the color sketch.[46] Some animators prefer erasable color pencils as opposed to graphite pencils because they do not smudge as easily, and the different colors allow for better separation of objects in the sketch.[47] Copy-editors find them useful too as markings stand out more than those of graphite, but can be erased.

Non-reproduction

Also known as non-photo blue pencils, the non-reproducing types make marks that are not reproducible by photocopiers[48] (examples include “Copy-not” by Sanford and “Mars Non-photo” by Staedtler) or by whiteprint copiers (such as “Mars Non-Print” by Staedtler).

Stenography

Stenographer‘s pencils, also known as a steno pencil, are expected to be very reliable, and their lead is break-proof. Nevertheless, steno pencils are sometimes sharpened at both ends to enhance reliability. They are round to avoid pressure pain during long texts.[49]

Golf

Golf pencils are usually short (a common length is 9 cm or 3.5 in) and very cheap. They are also known as library pencils, as many libraries offer them as disposable writing instruments.

By shape

- Triangular (more accurately a Reuleaux triangle)

- Hexagonal

- Round

- Bendable (flexible plastic)

By size

Typical

A standard, hexagonal, “#2 pencil” is cut to a hexagonal height of 6 mm (1⁄4 in), but the outer diameter is slightly larger (about 7 mm or 9⁄32 in) A standard, “#2”, hexagonal pencil is 19 cm (7.5 in) long.

Biggest

On 3 September 2007, Ashrita Furman unveiled his giant US$20,000 pencil – 23 metres (76 ft) long, 8,200 kilograms (18,000 lb) with over 2,000 kilograms (4,500 lb) for the graphite centre – after three weeks of creation in August 2007 as a birthday gift for teacher Sri Chinmoy. It is longer than the 20-metre (65 ft) pencil outside the Malaysia HQ of stationers Faber-Castell.[50][51][52]

By manufacture

Mechanical

Mechanical pencils use mechanical methods to push lead through a hole at the end. These can be divided into two groups: with propelling pencils an internal mechanism is employed to push the lead out from an internal compartment, while clutch pencils merely hold the lead in place (the lead is extended by releasing it and allowing some external force, usually gravity, to pull it out of the body). The erasers (sometimes replaced by a sharpener on pencils with larger lead sizes) are also removable (and thus replaceable), and usually cover a place to store replacement leads. Mechanical pencils are popular for their longevity and the fact that they may never need sharpening. Lead types are based on grade and size; with standard sizes being 2.00 mm (0.079 in), 1.40 mm (0.055 in), 1.00 mm (0.039 in), 0.70 mm (0.028 in), 0.50 mm (0.020 in), 0.35 mm (0.014 in), 0.25 mm (0.0098 in), 0.18 mm (0.0071 in), and 0.13 mm (0.0051 in) (ISO 9175-1)—the 0.90 mm (0.035 in) size is available, but is not considered a standard ISO size.[citation needed]

Pop a Point

Pioneered by Taiwanese stationery manufacturer Bensia Pioneer Industrial Corporation in the early 1970s, Pop a Point Pencils are also known as Bensia Pencils, stackable pencils or non-sharpening pencils. It is a type of pencil where many short pencil tips are housed in a cartridge-style plastic holder. A blunt tip is removed by pulling it from the writing end of the body and re-inserting it into the open-ended bottom of the body, thereby pushing a new tip to the top.

Plastic

Invented by Harold Grossman[53] for the Empire Pencil Company in 1967, plastic pencils were subsequently improved upon by Arthur D. Little for Empire from 1969 through the early 1970s; the plastic pencil was commercialised by Empire as the “EPCON” Pencil. These pencils were co-extruded, extruding a plasticised graphite mix within a wood-composite core.[54]

Other aspects

- By factory state: sharpened, unsharpened

- By casing material: wood, paper, plastic

- The P&P Office Waste Paper Processor recycles paper into pencils[55]

Health

Residual graphite from a pencil stick is not poisonous, and graphite is harmless if consumed.

Although lead has not been used for writing since antiquity, such as in Roman styli, lead poisoning from pencils was not uncommon. Until the middle of the 20th century the paint used for the outer coating could contain high concentrations of lead, and this could be ingested when the pencil was sucked or chewed.[56][additional citation(s) needed]

Manufacture

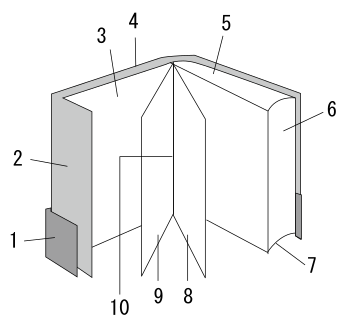

The lead of the pencil is a mix of finely ground graphite and clay powders. Before the two substances are mixed, they are separately cleaned of foreign matter and dried in a manner that creates large square cakes. Once the cakes have fully dried, the graphite and the clay squares are mixed together using water. The amount of clay content added to the graphite depends on the intended pencil hardness (lower proportions of clay makes the core softer),[57] and the amount of time spent on grinding the mixture determines the quality of the lead. The mixture is then shaped into long spaghetti-like strings, straightened, dried, cut, and then tempered in a kiln. The resulting strings are dipped in oil or molten wax, which seeps into the tiny holes of the material and allows for the smooth writing ability of the pencil. A juniper or incense-cedar plank with several long parallel grooves is cut to fashion a “slat,” and the graphite/clay strings are inserted into the grooves. Another grooved plank is glued on top, and the whole assembly is then cut into individual pencils, which are then varnished or painted. Many pencils feature an eraser on the top and so the process is usually still considered incomplete at this point. Each pencil has a shoulder cut on one end of the pencil to allow for a metal ferrule to be secured onto the wood. A rubber plug is then inserted into the ferrule for a functioning eraser on the end of the pencil.[58]

Grading and classification

Graphite pencils are made of a mixture of clay and graphite and their darkness varies from black to light grey. A higher amount of clay added to the pencil makes it harder, leaving lighter marks.[59][60][61] There is a wide range of grades available, mainly for artists who are interested in creating a full range of tones from light grey to black. Engineers prefer harder pencils which allow for a greater control in the shape of the lead.

Manufacturers distinguish their pencils by grading them, but there is no common standard.[62] Two pencils of the same grade but different manufacturers will not necessarily make a mark of identical tone nor have the same hardness.[a]

Most manufacturers, and almost all in Europe, designate their pencils with the letters H (commonly interpreted as “hardness”) to B (commonly “blackness”), as well as F (usually taken to mean “fineness”, although F pencils are no more fine or more easily sharpened than any other grade. Also referred as “firm” by many manufacturers[63][64][65]). The standard writing pencil is graded HB.[66][b] This designation, in the form “H. B.”, was in use at least as early as 1814.[67] Softer or harder pencil grades were described by a sequence or successive Bs or Hs such as BB and BBB for successively softer leads, and HH and HHH for successively harder ones.[68] The Koh-i-Noor Hardtmuth pencil manufacturers claim to have first used the HB designations, with H standing for Hardtmuth, B for the company’s location of Budějovice, and F for Franz Hardtmuth, who was responsible for technological improvements in pencil manufacture.[69][70]

As of 2021, a set of pencils ranging from a very soft, black-marking pencil to a very hard, light-marking pencil usually ranges from softest to hardest as follows:

| Tone and grade designations | Character | Application examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | US | RUS | ||

| 9B | – | – | extremely soft, black | for artistic purposes:sketchesstudiesdrafts |

| 8B | – | – | ||

| 7B | – | – | ||

| 6B | – | – | ||

| 5B | – | – | ||

| 4B | – | – | ||

| 3B | – | 3M | soft | freehand drawingwriting (restricted) |

| 2B | #0 | 2М | ||

| B | #1 | M | ||

| HB | #2 | TM | medium | writinglinear drawing |

| F | #2½* | – | ||

| H | #3 | T | hard | technical drawingmathematical drawing |

| 2H | #4 | 2T | ||

| 3H | – | 3T | very hard | technical detailed plansgraphical representations |

| 4H | – | – | ||

| 5H | – | – | ||

| 6H | – | – | extremely hard, light grey | for special purposes:lithographycartographyxylography |

| 7H | – | – | ||

| 8H | – | – | ||

| 9H | – | – | ||

| *Also seen as 22/4, 24/8, 2.5, 25/10 | ||||

Koh-i-noor offers twenty grades from 10H to 8B for its 1500 series.[71] Mitsubishi Pencil offers twenty-two grades from 10H to 10B for its Hi-uni range.[72] Derwent produces twenty grades from 9H to 9B for its graphic pencils.[73] Staedtler produces 24 from 10H to 12B for its Mars Lumograph pencils.[74]

Numbers as designation were first used by Conté and later by John Thoreau, father of Henry David Thoreau, in the 19th century.[c] Although Conté/Thoreau’s equivalence table is widely accepted,[citation needed] not all manufacturers follow it; for example, Faber-Castell uses a different equivalence table in its Grip 2001 pencils: 1 = 2B, 2 = B, 2½ = HB, 3 = H, 4 = 2H.

Hardness test

Graded pencils can be used for a rapid test that provides relative ratings for a series of coated panels but cannot be used to compare the pencil hardness of different coatings. This test defines a “pencil hardness” of a coating as the grade of the hardest pencil that does not permanently mark the coating when pressed firmly against it at a 45 degree angle.[d][75] For standardized measurements, there are Mohs hardness testing pencils on the market.

External colour and shape

The majority of pencils made in the US are painted yellow.[e] According to Henry Petroski,[76] this tradition began in 1890 when the L. & C. Hardtmuth Company of Austria-Hungary introduced their Koh-I-Noor brand, named after the famous diamond. It was intended to be the world’s best and most expensive pencil, as the ends of the pencil was dipped in 14-carat gold,[77] and at a time when most pencils were either painted in dark colours or not at all, the Koh-I-Noor was yellow. As well as simply being distinctive, the colour may have been inspired by the Austro-Hungarian flag; it was also suggestive of the Orient at a time when the best-quality graphite came from Siberia. Other companies then copied the yellow colour so that their pencils would be associated with this high-quality brand, and chose brand names with explicit Oriental references, such as Mikado (renamed Mirado)[f][g] and Mongol.[78][h]

Not all countries use yellow pencils. German and Brazilian pencils, for example, are often green, blue or black, based on the trademark colours of Faber-Castell, a major German stationery company which has plants in those countries. In southern European countries, pencils tend to be dark red or black with yellow lines, while in Australia, they are red with black bands at one end.[79] In India, the most common pencil colour scheme was dark red with black lines, and pencils with a large number of colour schemes are produced.[80]

Pencils are commonly round, hexagonal, or sometimes triangular in section. Carpenters’ pencils are typically oval or rectangular, so they cannot easily roll away during work.

Manufacturers

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Prominent global manufacturers of wood-cased (including wood-free) pencils:

| Manufacturer | Country of origin | Remark |

|---|---|---|

| Caran d’Ache | Switzerland | |

| China First Pencil Co. | China | “Chung hwa” and “Great Wall” brands |

| Cretacolor Bleistiftfabrik | Austria | |

| Derwent Cumberland Pencil Company | UK | Derwent brand |

| Dixon Ticonderoga | USA | Dixon, Oriole, Ticonderoga brands (manufactured in Mexico, China) |

| Faber-Castell AG | Germany | Plants in Germany, Indonesia, Costa Rica, Brazil, Malaysia |

| FILA Group | Italy | Temagraph, Lyra, Dixon, Ticonderoga, DOMS brands |

| General Pencil Co. | USA | General’s, Kimberly brands |

| Hindustan Pencils | India | Apsara, Nataraj brands |

| Koh-i-Noor Hardtmuth | Czech Republic | Koh-i-Noor brand |

| Lyra Bleistift-Fabrik | Germany | Parent: FILA Group |

| Mitsubishi Pencil Company | Japan | Mitsu-Bishi, Uni brands |

| Musgrave Pencil Company | USA | |

| Newell Brands | USA | Paper Mate brand |

| Palomino | USA | Division of California Cedar Products |

| Staedtler Mars GmbH & Co. | Germany | Staedtler brand |

| Tombow Pencil Co. | Japan | includes MONO brand |

| Viarco | Portugal |